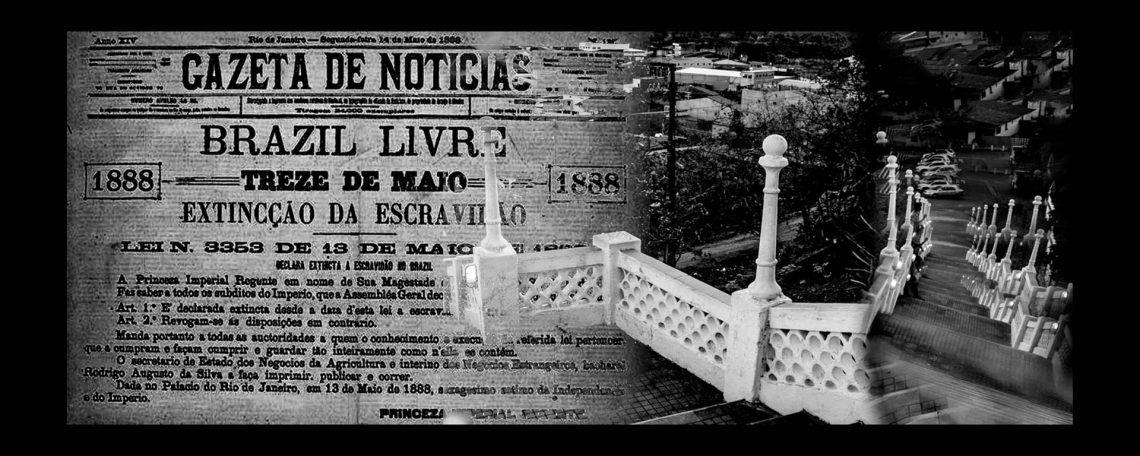

This work began in the early 2000s during a high school field trip to Redenção—Ceará’s first city to free enslaved people. Visiting the Museu Negro Liberto (Liberated Black Museum), I recall entering through the Casa Grande (master’s house): the spacious residence of a white family where textbook history materialized before me. Preserved objects and furniture filled its rooms; framed portraits displayed a social class’s luxury and impunity. Outside lay deactivated sugarcane mills, once powered by sweat and pain. To the left, a sign announced my first encounter with a senzala (slave quarters).

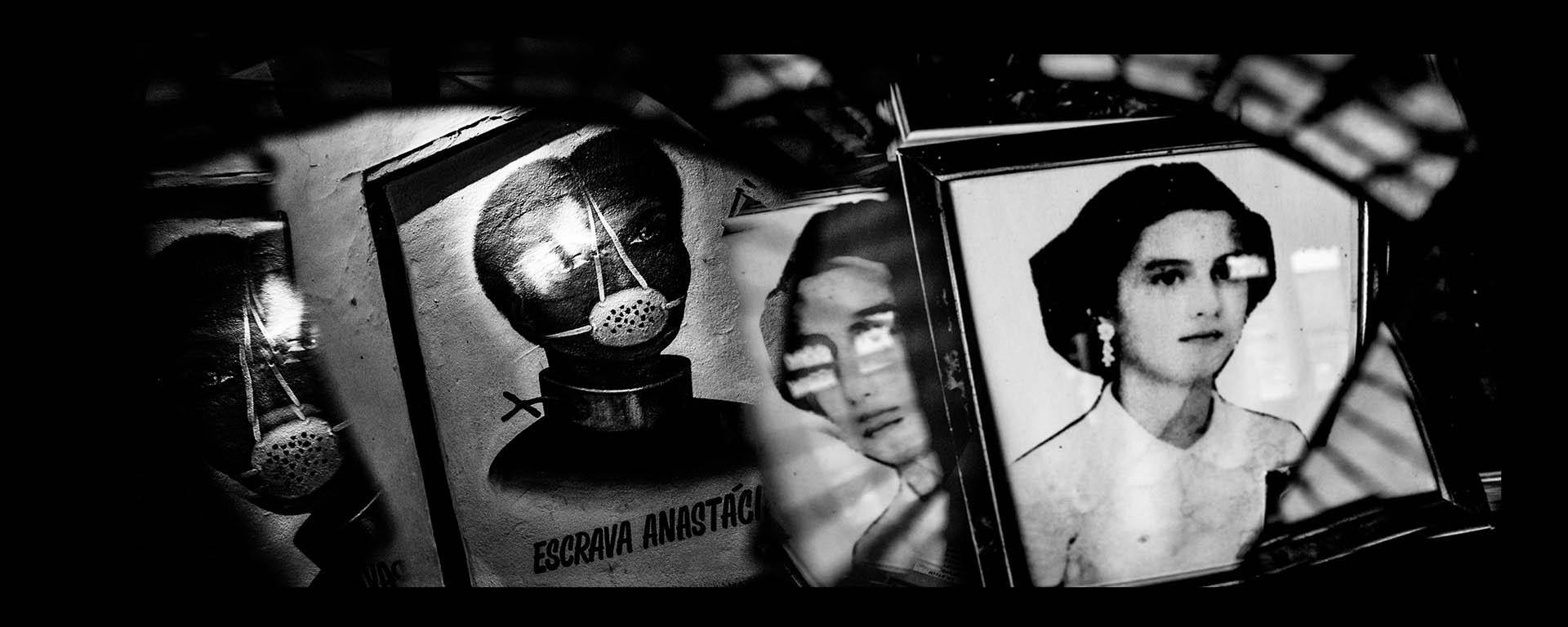

As large as the master’s house but doorless, its entrance was a small crawl-through hole. Inside: a dark space radiating panic, now home only to bats. Torture tools hung on walls. The air vanished from my lungs.

Profound discomfort consumed me, preventing full exploration. An unforgettable, shattering experience.

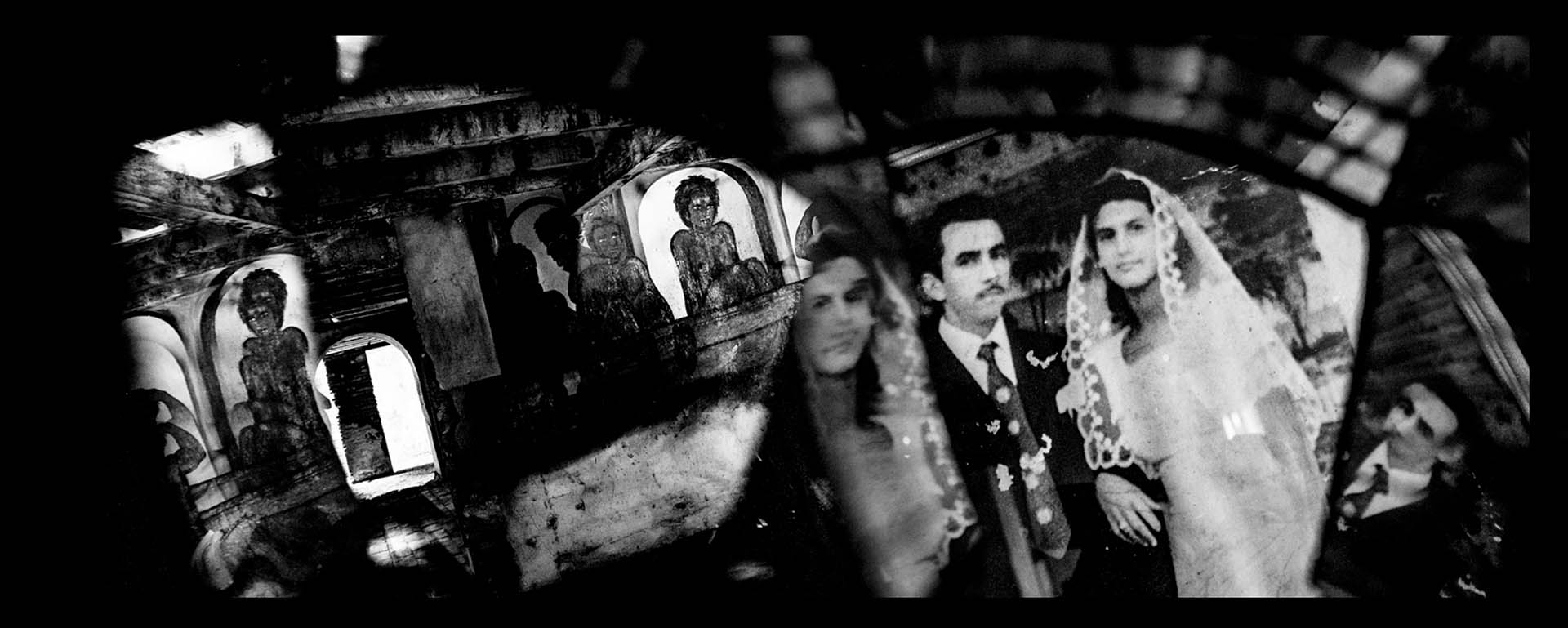

Over 21 years later, I returned to Redenção with fellow photographers. The museum remained unchanged—until the senzala. To my shock, it was transformed: a gate now opened to a light-filled entryway. Air circulated.

Torture tools were replaced by wall paintings depicting Black suffering. Venturing deeper (this time I could proceed), I found a white room with drawings of African deities: Exu, Ogum, Iansã, Iemanjá.

My controlled unease shattered when the guide declared: “This room honors the slaves,” adding, “They were good masters.”

From this discomfort, revolt, and white-hot indignation emerged images portraying two distinct realities within Brazil’s history—a history still romanticized by those who, out of shame, hide or erase immeasurable human cruelty.

Beware the history you narrate.

Translated with Deepseek AI