The relationship between philosophy and art has been a constant focus of reflection throughout human history. The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset was amazed to note how both disciplines have advanced hand in hand over time. Friedrich Hegel, for his part, argued that civilizations, societies, and individuals develop toward their fullness through philosophy, art, and religion. According to Hegel, a society reaches its peak when its philosophy has been fully developed; it is at that moment that a new society emerges through art, but at a higher level.

Within this framework, Pantagruel emerges as a project that seeks to illuminate this intrinsic relationship between philosophy and art, asserting the crucial importance of both disciplines in contemporary times. It is not merely a contemplative exercise, but a journey that leads us to catharsis through thought, a journey through the vast world of ideas. The philosophical idea that, from Plato to the present day, has been conveyed in a beautiful and poetic way by art. It is in this exchange of ideas, and as Markus Gabriel argues in his work The Power of Art (2018), our capacity to create art is what, in essence, defined us as humans.

Pantagruel unites art and thought with the aim of vindicating that human character that has allowed us to advance to the world we inhabit. Beyond the representation of ideas, the project aims to establish a dialogue with the viewer, demanding their active participation. Here, the viewer transcends their role as a mere observer to become an essential element of the work, closing the circle of meanings through interaction, debate, and reflection.

In The Dehumanization of Art, Ortega y Gasset introduces the concept of “art-artistic,” referring to art intended for sensibilities capable of perceiving the work in its full complexity. This sensitivity, in turn, becomes an art form in itself: the viewer is a necessary artist to complete the aesthetic experience. Similarly, Markus Gabriel emphasizes in The Power of Art the importance of the viewer as a co-creator of artistic meaning.

The name Pantagruel comes from a mysterious book published in 1565 by Richard Breton: Les songes drolatiques de Pantagruel. Without any text, this volume displays 120 illustrations of enigmatic creatures, which veer between the comical and the sinister. The title alludes to the medieval “droleries” (drole = funny), extravagant and satirical figures that decorated the margins of 13th-century French manuscripts with no apparent relation to the text they accompanied. Naming the project this way seeks to connect the viewer with the satirical and ironic spirit of the images, without neglecting the possible second readings that emerge from them.

As an anecdote, it is worth noting that Salvador Dalí was inspired by this same book to create his 23 lithographs entitled The Capricious Dreams of Pantagruel (1983), which underscores the relevance and evocative power of this iconographic reference.

The arjé is the primordial philosophical concept that the pre-Socratic philosophers explored in their search for the essential: the basic element or fundamental principle of all things.

The title of the project, Pantagruel and the Arjé, reflects this same spirit of inquiry, delving into the relationships between different branches of knowledge: philosophy, art, politics, science, religion, among others.

Pantagruel and the Arjé not only seeks to trace these links but also to raise new questions about the origin and interconnectedness of human thought, inviting the viewer to participate in this limitless exploration.

The work Pantagruel is born from a combination of self-portraits in digital photography and photomontages, without this combination establishing a hierarchy between the two resources. Elements such as the coat, the hat, and the mustache serve an aesthetic function, stripping the character of his individual identity and transforming him into a symbol.

In essence, Pantagruel is an excuse, an alter ego that allows the artist to take the necessary distance to foster a dialogue with the viewer about the world of ideas and philosophy. In this interplay of perspectives and meanings, the work not only questions but also challenges us to be an active part of contemporary thought and aesthetics.

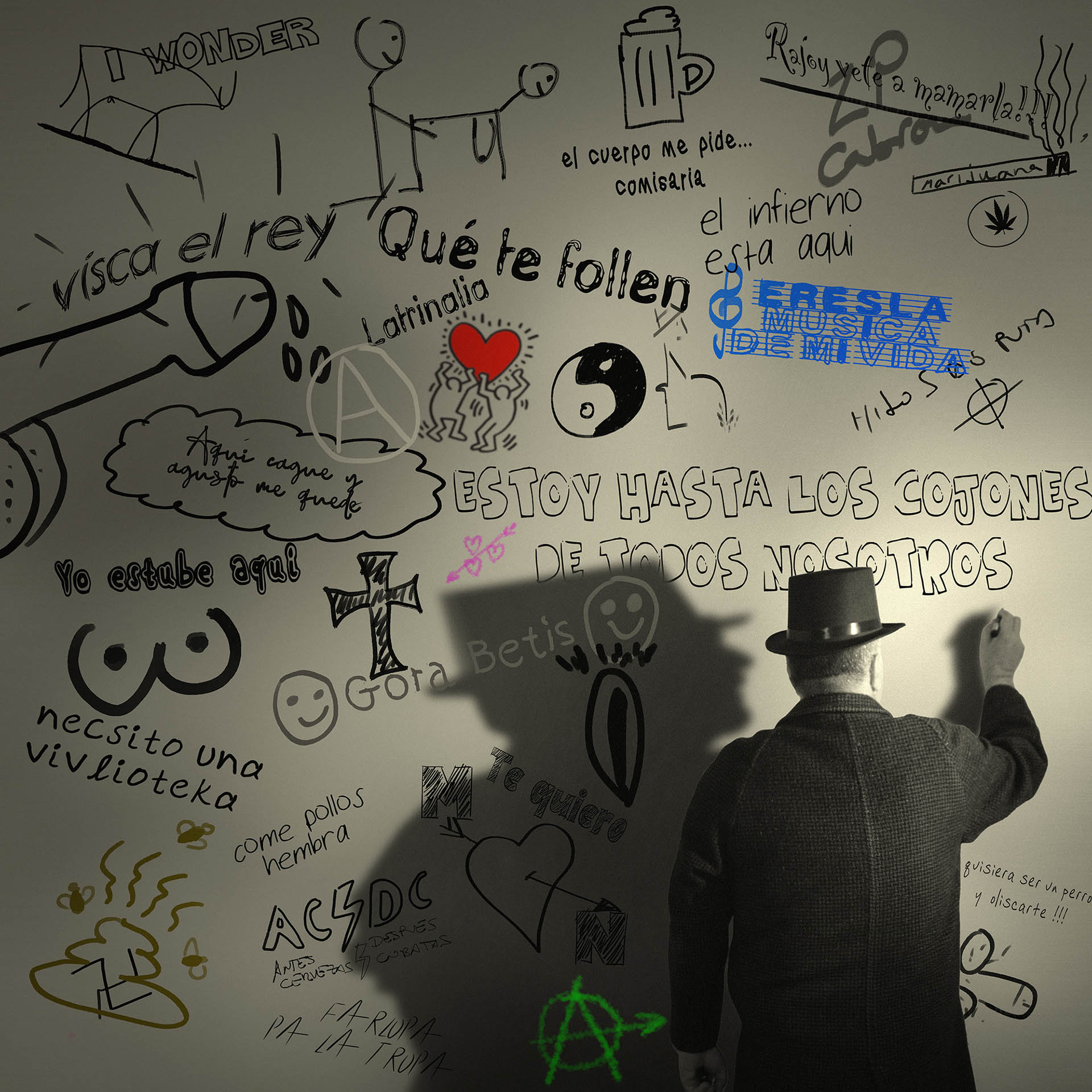

Latrinalia, a term coined by Alan Dundes in 1966, refers to a type of artistic expression characterized by messages and paintings with crude or obscene content, which some might describe as trash. These writings or drawings, generally found on the doors and walls of public restrooms, often address sexual and political themes, among others.

It is a “multi-authored” work born from anonymous imprinting, similar to the bison painted in prehistoric caves, which together can generate an unparalleled aesthetic experience. If “everything is art” and “we are all artists,” as Markus Gabriel argues in his book The Power of Art, should a latrinalia also be one?

Today, given the great diversity of artistic disciplines, the enormous number of artists, and the sheer number of works, the concept of art has become diluted for the layman’s eye. Frequently, when faced with new contemporary art proposals, the question arises as to whether a work should be considered artistic. This photograph seeks to spark this debate and reflect with the viewer on what we should consider art and what not.

The work challenges and engages the viewer as an indispensable part of the artistic composition: the work, the space, and the viewer as co-creator of the work of art.

In the image, Pantagruel appears on the wall of an imaginary public restroom, ironically sharing the widespread disgust with certain works or artists. He includes himself in the critique with the phrase: “I’m fed up with all of us.”

The photograph also conceals a small, intended homage to Picasso and Keith Haring. Technique: Digital photography + matte painting digital retouching

The Epic of Gilgamesh was written around 2500 BC and is considered the oldest known epic work. It narrates the adventures of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, a despotic monarch who must confront Enkidu, a wild man sent by the gods as punishment for his tyranny. After several battles without either being able to defeat the other, they eventually forge a deep friendship. Together they experience numerous adventures until the gods, outraged by his impious actions, decide to take Enkidu’s life. Devastated by the loss of his friend, Gilgamesh sets out in search of immortality, which, he is told, is found in a flower. However, he ultimately returns to his village empty-handed, realizing that immortality is a privilege reserved only for the gods.

The photograph expresses the idea that, after more than 4,500 years of knowledge, humanity has found that flower. We have learned to overcome death because we manage to stay alive in the memories of others. Technique: Digital photography

In this interest in searching for the concept of art and the way we have used it to share ideas in the most beautiful and poetic way throughout history, a specific artistic discipline is sometimes limited in expressing everything the artist wishes to express.

In 1890, Richard Wagner reflected on the work of art as a key concept in his aesthetic thought, saying:

“I wondered what the conditions of art should be so that it could inspire inviolable respect in the public, and in order not to venture too far into the examination of this question, I went to look for my starting point in ancient Greece. There I found the artistic work par excellence, the drama, where the idea, however sublime, however profound, can be expressed with the greatest clarity and in the most universally intelligible form.”

I realized, in effect, that wherever one of these arts reached its insurmountable limits, the sphere of action of another immediately began with the most rigorous exactitude, which consequently, through the intimate action of these two arts, would express with more satisfactory clarity what each of them could not express separately, that on the contrary, any attempt to achieve with the means of one of them what could not be achieved except by the combination of both must inevitably lead to obscurity, to confusion first, and then to the degeneration and corruption of each art in particular.”

Continuing with this same multidisciplinary intention, the photo hides a tribute to a well-known singer (Antonio Vega), which the more technical viewer can understand through reading the score and the flower.

Technique: Digital photography + digital retouching

In this interest in uniting art and philosophy, the photo clearly references Plato’s famous Myth of the Cave. It shows us the paradoxes produced by the absence of reality.

We also define shadow as “the dark projection that a body casts in the opposite direction to that from which it receives light.” Thus, in the history of symbolism, this “dark projection” is understood as something negative. In that darkness, the negative side of ourselves can be found, all our dark secrets. It’s a memory of Peter Pan trying to catch his rebellious shadow.

The photo lacks a title precisely because it aims to generate multiple debates: the duality of the self, determinism and freedom, identity, the paradox of time, etc.

Technique: Digital photography + photomontage

Reflection on the self and identity has been a central question in the history of human thought, addressed from multiple philosophical perspectives. From Plato, who argued that the soul is the true self, to thinkers in Buddhism and Hinduism, where identity is a manifestation of the whole. Currently, thinkers such as Byung-Chul Han have analyzed the crisis of the self in contemporary society in his book The Society of Fatigue, trapped in the logic of performance and self- exploitation.

The photograph poses precisely this dilemma: the search for identity in a world where the individual seems fragmented, incomplete, reduced to a cog in a larger machine. The image suggests a critique of the polarization of ideas and thought, of the dissolution of individuality within collective structures that impose identity patterns. In an age where social media, mass culture, and hyperconnectivity lead us to define ourselves through the eyes of others, are we really who we think we are or just pieces fitted into an imposed puzzle?

Technique: Digital photography + photomontage and digital retouching

“A Trip to the Moon” is a 1902 film directed by Georges Méliès, inspired by various literary and scientific sources. Among them, Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon (1865) stands out, as well as H.G. Wells’s The First Men in the Moon (1901). This pioneering work not only marked a milestone in the history of cinema, but also symbolized the human capacity to dream of the impossible and represent it visually long before space exploration was a reality.

Paleontologist Ignacio Martínez Mendizábal argues that what truly made us human was our ability to conceive ideas: “it was that idea that was the tool with which we were able to assault the future.” It wasn’t just manual dexterity or technical intelligence, but imagination and the projection of what didn’t yet exist that set us apart from other species.

The photograph pays homage to precisely that faculty: imagination as the driving force of humanity. Throughout history, humankind has imagined, conceived, and pursued ideas that at one time seemed unattainable, unrealizable, or the stuff of fantasy. However, thanks to tenacity, hard work, and passion, many of those dreams have eventually become reality.

Today, like Méliès more than a century ago, we continue to travel to the Moon, not only with spacecraft, but with the power of our ideas.

Technique: digital photography + digital retouching

This photo is a critique through visual metaphor and questions certain types of thinking and ideas. Spanish professor and philosopher José Antonio Marina wondered if all opinions are equally respectable, to which he himself replied that they are not. What is respectable is the right to be expressed without censorship, but the respectability of opinions depends on their content. There are stupid, blasphemous, racist, and xenophobic opinions that, even though they have the right to be expressed, do not have the right to be respected.

Technique: Digital photography + photomontage

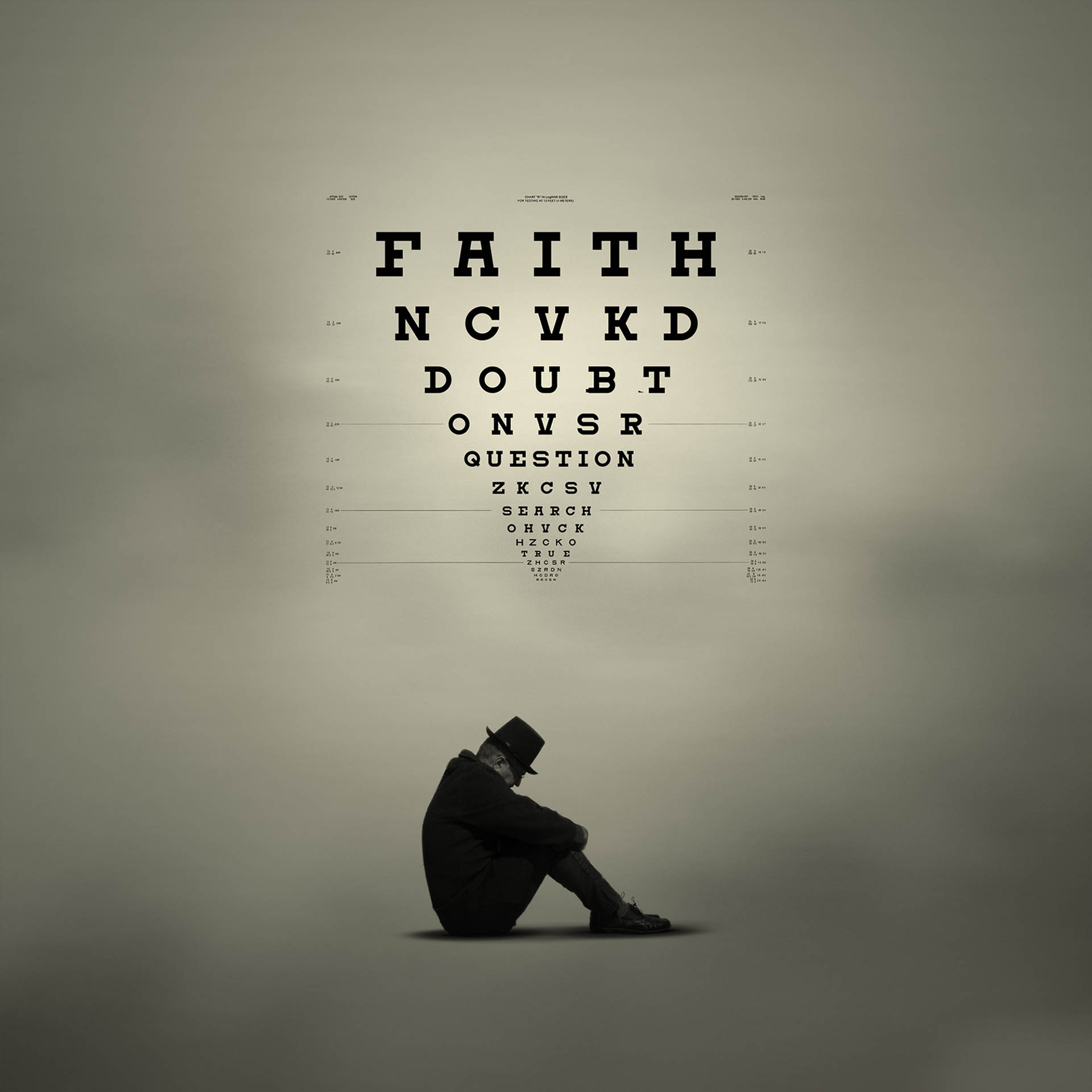

The evolution of human knowledge is a journey that many thinkers have agreed to call the path from myth to logos. In that first stage, we leave the answers to all our questions in the hands of the gods and find in them the simplest way to explain everything we were unable to understand. With the birth of philosophy and later science, we achieved other milestones in knowledge.

The photo is a metaphor that visualizes this path and the effort it has taken us to travel that road. Through the famous Snellen test, we can easily see faith. With a little more attention, we can see doubt and mistrust further down. To see the question further down, we need a little more effort. The search requires an effort, in this case, visual effort. Finally, there is the truth below and in small print, which is visible only to very few.

The photo is an allegory of the intellectual effort required to reach authentic knowledge. Technique: Digital photography + photomontage

This is a dreamlike photograph, also untitled, with the intention of leaving the viewer the necessary space to create their own dream, their own story, the viewer as co-creator of the work of art. The famous Spanish photographer Jose Antonio Navia once commented that a photograph is hardly worth a thousand words, but that a photograph is capable of being the spark that ignites and illuminates a thousand and one different stories, somewhat in the same vein as Susan Sontag’s statement in her legendary book On Photography, where she commented, “There are not many photographs that are worth a thousand words.”

The photograph is born from multiple ideas. Among others, a critique of our relationship with the world and nature and a possible dystopian future that lurks before us. The paradox of continuing to feed a horse as a symbol of success and the spirit that has become a papier-mâché object.

TECHNIQUE: DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY + PHOTOMONTAGE